Dear Readers: For those of you who are curious about the book, I’ll be posting most of it over the next few months. Thus every Monday I’ll post a large portion of each chapter. Glean what you want from this. I own the copyright so can share it however I please. I’ve been told by a lot of artists and instructors that LTAL has been very helpful to them. Hope the same proves true for you.

Best,

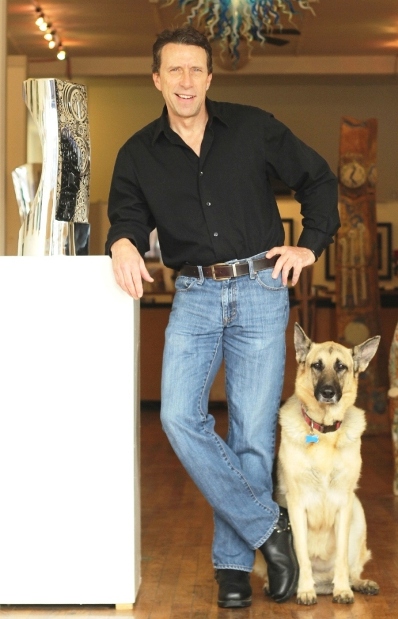

Paul

CHAPTER 1

Who Am I?

I’m a gallery owner and art advisor, as I have been since 1991. Over the years I’ve been fortunate enough to rack up many accomplishments, which were built on the wreckage of multiple failures. In the business sense, the aesthetic sense, and the giving sense, I suppose I’m considered a success. That’s cool, but that state of success was preceded by a lifetime of artistic and financial struggle—bounced checks, creative frustration, black despair, and hundreds of rejections for myself and my artists.

Why rejections for myself? I’m a novelist. Writing is the primary passion of my life—driven, maddening, fulfilling, by turns sane and insane. Just as many of you can’t live without painting or sculpting, I can’t live without writing. The only reason I got into the art business was to support my family on the road to publication, which says a lot about my initial naiveté in both professions. But I got into this gig to succeed, and so undertook it with the same passion with which I write. I also got into it to make a difference in my part of the world, not just make a buck.

Have our successes come easily? No, for me they took decades of sacrifice, dedication, and very long hours. Was it all worthwhile? In some ways yes, in others no – all achievements have their price. My artists and I have paid that price, just as everyone must—usually throughout our lives.

Why have I written this? To help you succeed as an artist. The definitions of your success—whether aesthetic, rebellious, monetary, or all of these—are up to you. My job is to assure you that you can achieve your goals, and to assist with their realization. This book, based on all my years of experience, can help you do just that. I’ve been immersed in the arts since the ‘70s; many of my artists since the ‘60s. Collectively we’ve learned a great deal along the way.

Is this book only for artists? No. I’ve written it for the student and teacher, the writer and reader, the gallery owner and collector, and anyone else who lives within the world of creative drive. Further, the things I’m going to cover are not typically taught on campuses. Why? Because while art professors are greatly skilled at what they do—guiding raw talent toward mastery—most have never run a gallery. Why would they? That isn’t their profession, any more than to instruct in painting is mine. But unless you’ve managed a gallery, with all the risks and challenges that come with one, it’s not possible to fully teach about building a career that works. Both points of view, and both realms of experience, are essential.

And by teach I don’t mean perpetuating shopworn methods that usually lead nowhere. I mean cutting through the bull, being honest about what works and what doesn’t, and understanding why the art business, as it has traditionally been structured, is more often a recipe for failure than success.

Over the course of my gallery’s existence I’ve caused roughly $12 million to be invested in the artists of my region, about half of this through projects I’ve overseen, the other half through gallery sales. Is that big money? When compared to those rare dealers who routinely trade in the millions, no. But for the rest of us who struggle just to pay the rent, this series of feats have far exceeded my initial goals. They’ve allowed me to live the dream, though during the initial years it seemed more of a nightmare.

Now when a gallery begins to succeed in selling art, does that make it commercial—assuming that the work it carries is not? No more than when an indie film succeeds. You don’t compromise on the art; you create a market for it, however edgy it might be. Yet when an artist begins to sell well, their work and the galleries that carry it are often branded this way. This exemplifies a common dilemma in the arts, including music. The majority of all artists want to sell, but once they begin to, they’re sometimes ostracized by their peers.

Why? Because certain snobs look down upon the business of selling, as though it degrades the work. What, so it’s better to starve? Interestingly, I’ve noticed that people who have this view often are not artists, which basically makes them armchair quarterbacks, since if you’re not on the field, you can’t comprehend the risks of the struggle. Van Gogh would have given anything to sell just one painting. Warhol sold very well, and inevitably came under fire for doing so.

Where does this contradictory view come from? I believe it’s rooted in the fact that artists never want to see their work associated with a retail business—which they shouldn’t. Art creation should take place outside the market, driven exclusively by passion, vision, and a little bit of hell-raising where needed. However once a piece has been delivered to a gallery, it has indeed been delivered to a retail business. Frankenthaler understood this, Magritte understood this, and Picasso understood it best of all.

If a gallery is to be run competently, it must be businesslike. And like any firm, it must have a marketing plan, accurate bookkeeping, public relations skills, sophisticated graphics, annual projections, satisfied creditors, and the ability to convince collectors to invest repeatedly in new artists, so that those artists can pay their rent. Yet a gallery, like a publisher, is often also a place of idealism—lofty philosophies, lofty goals, a group of people working toward a common end that is bigger than they. This is the orientation of my place. But we’re a business first, since if we don’t succeed, nothing is advanced and all our families suffer—meaning those of my artists as well as my own. In this wealthiest of nations, I’ve never found that acceptable as an option.

My point? Unless a dealer can get collectors to pay a respectable sum for the work of artists in their region, then the arts there aren’t being advanced. No sort of commerce can grow without the investment of capital, and neither can the arts. When all the well-intended talk is over, if private and corporate collectors aren’t putting money on the barrelhead, it’s just lip service. Far better for accomplished artists to be paid what they’re worth. Your region in general will benefit from that in terms of cultural growth—schools, corporations, institutions, and other disciplines in the arts. Cultural growth, throughout the country, is what I’m most interested in. This is at the heart of what I call the Regional Renaissance—a concept we’ll get to later.

Convincing collectors to put down real money for art is a challenge I’ve been dealing with for decades, and I’ve done the bulk of it in the Midwest—an area not always known for impassioned collecting. My drive to achieve this has helped bring us a plethora of projects—an enormous collection for H&R Block in virtually all media; an eighty-five-foot sculpture in blown glass for the University of Kansas Hospital; a sculpture in stainless steel for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; dozens of works both large and small for a convention center in Kansas City; all monumental sculpture for the National D-Day Memorial in Virginia; a monument of Mark Twain in Hartford; paintings for restaurants and hotels; a monument for the Capitol Building in DC; and thousands of works for private collectors. Steven Spielberg has acquired art through my gallery, as did Charles Schulz and Douglas Adams.

What have I sold these people? A wide variety of art, since I believe that well-executed contemporary, conceptual and representational works are all legitimate. I’ve never been interested in debates about the opposing worth of these disciplines. To me, certain of these approaches advance new frontiers while others maintain critical standards. If I’m going to spend time arguing, it would be about the need to curb poverty and offer opportunities to low-income teenage artists, rather than debating the merits of Duchamp’s Readymades as opposed to Monet’s landscapes. To me, both have their place.

Who Are You?

By this, I mean what are your goals? Do you want to get accepted in juried exhibits? Do you want gallery representation? Do you want representation in more than just your region? Would you like to make a profit from your work? Do you want to give it away? Do you want to shock people? Inspire them? Amuse them? All of these are legitimate goals. I’m just urging that you define yours—although of course you likely already have.

Then after you answer those questions, consider these: Are you content with your work? Do you feel you’re pulling the best out of your guts that you can? Do you sometimes curse your fate, wondering why you were born with this inexplicable drive that society so rarely appreciates? Do you sometimes want to pack the whole thing in, only to find you can’t? Are you still wondering if you’re good enough, no matter how many years you’ve been working?

Welcome to the family—all this is part of our makeup, it’s just rarely discussed. But it’s when we address the rarely discussed and taboo that we often learn the most.

Something else—regardless of what kind of artist you are, please never forget that art—music, painting, writing, sculpting, creating—is a cornerstone of any civilized society. In fact the nonconformity that art usually springs from is an essential part of any democracy, since no society can progress without a healthy sector of nonconformity. After all if we didn’t have nonconformists, we’d still have slavery.

Is the artist’s purpose frivolous then? No. It’s just as significant as that of the farmer, the architect, the philosopher, the physician, the legislator, and the teacher. Those roles are all interwoven, not one of them more substantial than the other, each with its own critical weight. We are here, you and I, to make sure that society never forgets our place in that roll call.

Wonder Bread, Seven-Grain, and the Regional Renaissance

When I was growing up in Kansas City in the ‘60s, our cultural life was much like the Wonder Bread the schools gave us to eat—bland, unoriginal, devoid of passion. For years I thought this was confined to my part of the country, but as I began to travel, I learned it was a national malaise. Gradually I realized that the malaise had existed even in places like Westchester and Marin County. Only in certain pockets—Greenwich Village, Central Chicago, North Beach—had it been any different. Oh every city had its art movement, no matter how small, but the impact this had on the rest of each city was minimal, primarily because these movements tended to be centered in bohemian enclaves whose participants were written off as weird.

But now this country is going through a Regional Renaissance unlike anything in its past. In every region—the Midwest, the South, the rural West—art creation is assuming a life of its own outside New York and Los Angeles. What does this mean? For painters and sculptors who for years were told that if they weren’t showing in Soho, they didn’t count, the story has changed.

The art world is no longer centered in New York, but began dispersing across the country in the ‘90s, a movement that was much facilitated by the Internet. In Austin, Albany, Columbus, Sacramento, and hundreds of other towns, work is being created that could easily pass muster in Soho. Further, collectors in each region are beginning to participate. Ditto regional art centers, high schools, junior colleges, universities, arts commissions, and virtually every other entity in the game. These organizations, and the people who staff them, have worked for decades in bringing about this change. The beauty of it? Their efforts are paying off.

You can benefit from this renaissance. That’s why dealers like me have labored so hard in promoting the artists of our region. We were tired of being frozen out by the some of the more closed aspects of the elitist world—brilliant though it often is. So we created a world of our own.

When I was in grade school, my only experience with that world was when the Art Lady—a very kind but rather uninspired volunteer—would come to our class and in a nasal Midwestern accent discuss Monet and van Gogh. I’m not sure that she tapped our passions, but at least she made the attempt, which was more than the district was doing. The Shawnee Mission District, like most school districts at that time, spent a lot of money on football but little on the arts. And while SMD has since mended its ways to an extraordinary extent, at the time it was as imbalanced as most other districts nationwide.

My mother sensed the injustice of this, and tried to give us a deeper cultural grounding. This was at the same time that she discovered yoga and meditation, when fried food disappeared from our diets, and when concepts of positive thought were reinforced daily. Her journey, and the one she took us on with her, is a curious tale, but I have no room to discuss it here. I’ve done that in a novel, Cool Nation, which I suspect will appear in print one day.

So my mom, who our less imaginative neighbors thought nuts, gave my brothers, sisters and me a rare opportunity to explore individual growth. It was at this time that all Wonder Bread disappeared from our house, replaced by the seven-grain that she bought at a health-food store in Brookside. Not long after that she made each of us read Ram Dass’ Remember Be Here Now and other books of that ilk. She even asked my father to read it, which he did, then encouraged him to keep from mocking it, which he didn’t.

My dad, a bare-fisted contractor from the Ozarks, was shocked by the changes in his wife, but did his best to change in pace with her, hoping that if he did, it would save their marriage. Unfortunately, it did not.

Why do I mention this? Because in cities all over the country at that same time, other men and women were making similar discoveries. If they hadn’t, the renaissance we’re currently enjoying would not be taking place. Many of them did this at the price of ostracism, cruelty, and petty gossip that was damaging to themselves and their families. But for those who understood the worth of integrity and growth, none of those things mattered.

Ironically, the opportunities for those changes were rooted in two of the greatest tragedies of the Twentieth Century—the Great Depression and World War II. Had my parents’ generation not answered the savage challenges of those events, the seeds of prosperity that made the Regional Renaissance possible would never have sprouted. So my hat is off to that generation, and all the sacrifices they made—which many of them didn’t even survive to see the result of. And yet had it not been for the questioning nature of people like my mother, who were willing to listen to the generations that followed, we would never have known that a less conformist world existed, and would have apathetically gone on eating white bread for the rest of our lives.

Even so, this notion of rebelling against a conformist society was limited mostly to the middle and upper class. In the inner cities, especially among non-whites, the rebellion took on a different tone, since people there were primarily concerned with the rights they were being denied more than the freedom to express themselves. A cultural renaissance would gradually be felt in the urban areas too, but it would take decades for it to have much of an impact. That impact has been minimal, with opportunities for black and Hispanic artists still too few, but they are slowly growing.

What is the upshot of all this? For better or worse, the reins of the country are now in different hands. These generations tend to be more engaged in the arts and less shocked by nonconformity. I mean Cadillac recently ran a series of ads for which the background music was Led Zeppelin. Cadillac? This should tell you something. Those in charge now are juiced by the suggestion of nonconformity, even while certain of them are conformist in nature. In fact the byword for all things accepted, even at the executive level, has become Cool.

What does this mean for artists? A broader point of view, and a broader market, have opened up. No matter where you live, you can work with it. How? Keep reading and I’ll show you.